The American screenwriter and director David Mamet enjoys a reputation as one of the most hard-boiled characters in Hollywood. Over a 40-year career, he has created a veritable identity parade of conmen and crooks, from the real estate hustlers of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Glengarry Glen Ross to Gene Hackman’s underworld boss in Heist.

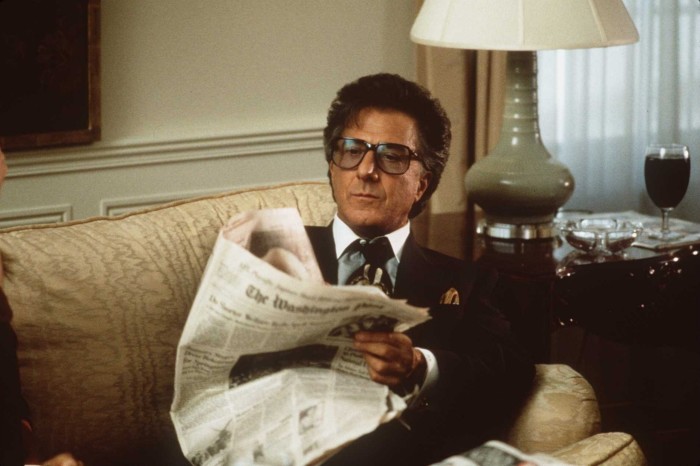

He has rattled over the faultlines of American society with the nerveless brio of a New York cabbie dodging potholes. Oleanna (1994), a story about a professor and the student who accuses him of sexual misconduct, was a bleak rehearsal of what was to come with #MeToo. Before anyone had heard of fake news, Dustin Hoffman in Wag the Dog (1997) was a PR man for whom the truth was as disposable as a coffee cup.

And yet for all of Mamet’s blackly comic worldliness, you only have to show him a little close-up magic, or a bit of business designed to misdirect an audience, and he’s as enthralled as the most gullible mark. He was a friend of the great magician Ricky Jay and cast him in his 1987 noirish thriller House of Games.

As much as Mamet is a sucker for a trick, he also relishes eavesdropping on a trick of the trade. When he was an out of work actor, he spent time in a realtor’s office in Chicago, which he drew on for the slick patter and subterfuges that he gave his fictional salesmen.

Now 76 and claiming that he has “aged out” of the film industry, Mamet has produced a book of “tell-alls, cartoons and captions. That is my version of the faded film idol taken to shoplifting as the sole remaining possibility of maintaining public notice.”

Everywhere an Oink Oink is his scratchy, funny and enlightening account of 40 years in the movies, which doubles as a handy primer for wannabe scriptwriters (though he’d hate me for saying so).

Mamet learnt his craft in the theatre and reveres the old-time stars who came up the same way. For those contemplating a career in show business, he recommends brutal, Darwinian experience over book-learning, quoting Jay’s hard-won insight: “You never know your show till everything than can go wrong has.” Nonetheless, the aspiring actor or screenwriter could do a lot worse than read Mamet between waiting tables or flipping burgers.

He explains how he solved a problem in the third act of a kidnap drama for director Martin Scorsese (“who I’d turned down for Raging Bull”). The answer didn’t lie with the filthy-rich businessman who was being pressed for the ransom, Mamet decided, but with his spoilt son who was the abductors’ target.

However, he writes that the film’s producers had already decided the father was the bad guy. “‘No, no’, they said, slurping their blinis with caviar (I swear), ‘he has to be punished for his greed’.” Producers emerge as the bad guys of this book: liabilities and hangers-on, for the most part. And Mamet should have known better than to think he could convert them to his point of view, especially at lunch. “Nobody in Hollywood ever changed his mind,” he claims.

You wonder how Mamet’s 40 or so scripts, two of them Oscar-nominated, ever got written. If he isn’t getting bumped from a project, he’s walking off it, because he refuses to contemplate changing a single word. He’s scornful of the quick fix of script doctoring: a car chase here; a love scene there. “This is the understanding of an amateur. The Professional (myself) addresses the script as a problem in construction — just as the magician plots an effect.”

Readers with little interest in the movies can still pick up valuable insights into the business called show. Mamet recounts the unlikely rise of a dry cleaner who realised that his Hollywood clients settled his bills without looking at them. He began to pad them, and to move into dry cleaning for film productions. “He branched out into catering, car rental, costume rental” and eventually became the “fly-by-night producer” on a Mamet film.

According to the author, he was only doing what the big studios themselves got up to on an industrial scale: “They hid income from profit participants, even on huge moneymakers — they charged back ‘embedded’ costs from failed films of yore they had made.”

Is it Mamet’s orneriness that got him sidelined by the industry, you wonder, or his contempt for today’s filmmakers, who are too politically correct for his liking? In his opinion, Hollywood was built by “tough-guy Jews who were the business, the hard-drinking, hard-whoring gamblers and thugs who bit their nails over ‘offending’ majority Americans. Now the feared objects are not the mass but the minorities.” The movie business has lost its nerve, according to Mamet, afraid of what some section or other of the audience might disapprove of, and crassly reliant on superhero franchises, or “animated renditions of Norse Sagas”, as he calls them.

The script doctors whom Mamet disdains would probably recommend a rewrite for this memoir; it is wildly discursive in parts. But that would be like turning a blazing Klieg light on a magician as he performs his sleight of hand before our very eyes.

Instead, Mamet the magician plots his effects. After a line about show people being helpless recidivists (like criminals and politicians, “we can never go straight”), here’s his unexpected and self-mocking pay-off: “The rooms at Versailles were tiny, unventilated, filthy and dark, but the Nobility considered any other habitation exile.”

Everywhere an Oink Oink: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in Hollywood by David Mamet Simon & Schuster £20/$27.99, 256 pages

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen