A year into the DMA’s implementation, the European Commission is continuing to deliver findings adverse to U.S. tech giants. In late March, the Commission issued a decision specifying Apple’s interoperability requirements and released separate preliminary findings that Google failed to comply with the DMA’s self-preferencing and anti-steering obligations. The Commission’s actions in both cases reflect a continuing overreach into platforms’ ability to compete in Europe. With the EU making clear it can issue huge fines, it appears that the U.S. and EU are on the cusp of an unfortunate—but entirely preventable—confrontation over the DMA’s continued targeting of American tech companies.

Apple’s interoperability obligations concern nine features that link connected devices like smartwatches, headphones, or TVs to Apple’s iOS. As a general matter, the Commission mandates that Apple grant third-party connected devices the same level of access to these features as it does to its products, like AirPods, Apple Watch, and Apple Vision Pro.

One measure, for instance, requires Apple to treat competitors equally with respect to iOS notifications. In practice, this means that third-party devices like a Garmin watch must be granted the same notification functionalities as an Apple Watch, including the ability to receive and act on notifications, customize which are shown, and display related visuals and metadata.

While this may sound appealing in the name of user choice, forcing interoperability carries unnecessary risks to consumers and innovation. First, Apple already has a procedure for connected device makers to request interoperability features, and there is no reason to believe this process cannot address the Commission’s concerns without resorting to heavy-handed DMA enforcement. Second, obligations related to features like automatic Wi-Fi pairing compromise user privacy by creating an avenue for malicious third parties to extract sensitive data (e.g., Wi-Fi credentials) from Apple users.

Beyond threats to consumer privacy, compelling Apple to share its technology reduces its incentive to innovate and also encourages third parties to free ride on Apple’s handouts instead of developing their own solutions.

Moreover, the Commission’s interpretation of the DMA turns Apple into a de facto public utility. Whereas DMA Article 6(7) merely calls for “effective interoperability” for third parties, Apple’s obligations are tantamount to a nondiscrimination regime in which the company is required to build and maintain interoperability solutions that are “equally effective to those available to Apple” for any third-party connected device provider—even if doing so is not necessarily technically feasible or practical.

Traditional European competition law in TFEU Article 102 generally applies a standard of protecting a competitor “as efficient as the dominant undertaking” when evaluating abusive conduct. However, the Commission’s broad interpretation of effective interoperability for Apple goes above and beyond this, basically requiring that any connected device maker, regardless of efficiency or security, be able to access Apple’s interoperability features.

Fundamentally, the Commission’s approach inserts regulators into Apple’s boardroom, dictating engineering priorities without regard for Apple’s freedom to design its products. This sets a troubling precedent for global competition policymaking, one that prioritizes regulatory micromanagement over light-touch action. What’s more, some obligations rest on speculative assumptions about which interoperability features connected device makers need to compete, which may lead to flawed interoperability solutions.

In addition, Apple’s interoperability obligations under the decision will impose excessive costs on the company that it cannot even recoup by charging connected device makers a fee, meaning European consumers will likely bear those costs. Indeed, the decision also overlooks that Apple already provides extensive developer support, with over 250,000 APIs currently available. But forcing the company to build detailed documentation for each API atop this infrastructure, as the Commission now requires, imposes disproportionate costs on Apple that risk diverting resources away from, among other things, the innovation that Europe desperately needs.

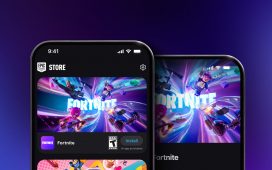

In addition to its crusade against Apple, the European Commission has found Google non-compliant with the DMA’s anti-steering rules. Specifically, the Commission expects Google to allow developers to include links to external websites where users can download apps from outside the Play Store’s secure environment. This will likely prove a boon to malicious actors, and whether the Commission fully grasps this risk is unclear. As Google notes, Android users already have access to an extremely open platform, and generally allowing external links would erode important protections for Play Store users, ultimately making it easier for scammers and data thieves to exploit user trust. What’s more, as with Apple, the Commission oversteps the bounds of traditional competition policy by asserting that Google charged developers high fees for digital purchases over an “unduly long” period, an accusation that goes beyond protecting competition and amounts to de facto price regulation.

Second, the EU continues to attack Google for favoring its own ancillary services in Search, such as Maps. Yet, Google has already taken significant steps to remove the problematic features in question, like the Flights and Maps toolbars. And, even though the Commission refuses to acknowledge it, these integrations serve an important pro-competitive function by helping consumers find relevant information more efficiently and offering business users valuable visibility. Indeed, removing these features has already caused real harm to users. For example, Google introduced the Places Sites feature to boost competing platforms like Yelp and Tripadvisor, but this came at the expense of restaurants, airlines, and hotels that have seen reduced traffic as a result.

At a time when the EU should be welcoming high-quality digital imports from the United States to help offset its soaring trade surplus, it is instead doubling down on the DMA and refusing to reconsider it as part of negotiations with the Trump administration. These growing U.S.-EU tensions play directly into China’s hands, as tech giants like Huawei, Alibaba, and Tencent expand globally under a protective industrial policy regime with minimal international scrutiny. Prime Minister Meloni’s recent visit to Washington and the progress toward a U.S.-EU trade deal, which could lay the foundation for a broader G2 alliance as ITIF has proposed, underscores what’s at stake. The DMA should be on the table. As such, the Trump administration must hold firm: If Brussels is allowed to weaken American firms through unchecked regulatory overreach, the biggest winner won’t be European consumers—it will be Beijing.