Key Takeaways

- Streaming revolutionized music consumption with accessibility but artists suffer low pay compared to CD sales.

- CD’s provided lossless audio while many iPods didn’t support high-quality files, unlike today’s streaming services.

- Streaming disincentivized piracy due to ease and social sharing aspects, making it a more appealing option than buying albums.

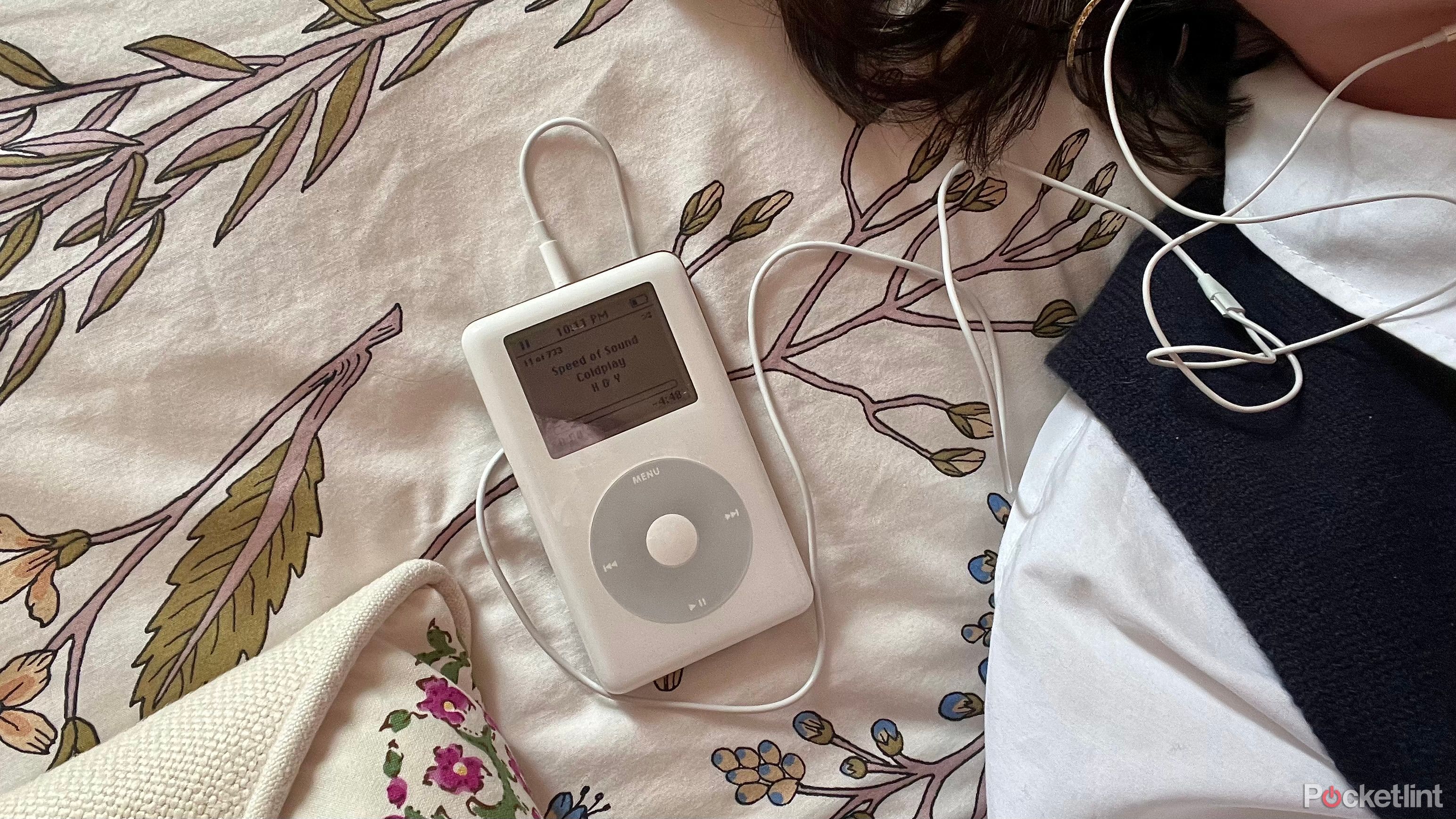

In 2001, Apple announced its revolutionary iPod. The sleek, compact device boasted 5GB of storage to hold “1000 songs in your pocket,” and it felt like something shifted. Personal media players had existed for years with the likes of the Walkman and Discman for playing physical media, and various early MP3 players had hit the market in the late 1990s. But the iPod took over the market and ushered in an iconic era of digital music listening, giving rise to other digital audio players like Microsoft’s Zune and SanDisk’s Sansa. Pretty much every tech company at the time tried their hand at making an MP3 player, with varying amounts of success.

Why removing the headphone jack was bad for wired headphones

But it’s not too late — not even the biggest companies on the planet can destroy a 140-year old port.

Back then, in the earlier days of the internet, our options for how to get our music came down to buying individual songs and albums on platforms like iTunes, buying physical CDs and burning them to put them on our MP3 players. Simply put, you had to seek out music and listen to it much more intentionally a lot of the time. Plus, music was costly. Individual songs at the time cost anywhere from 99 cents to $1.27, and albums ran between $10 to $20 each on CD. So, building up a catalog of music had a high upfront cost, and you were limited to 1,000 songs on the earliest iteration of the iPod, or less if the songs were particularly long.

I listened to my old iPod for a month, and it wasn’t the nostalgia trip I expected

I turned to my clunky iPod Classic for simpler listening, but it came with some complexities.

In 2006, Spotify was founded, launching in the UK in 2010 and the US in 2011, albeit in limited ways. It grew in popularity for years and eventually became the most popular way to listen to music online. I personally got my account through an invitation back in 2014, and I was in awe at the idea of it. It almost felt unfeasible, or somehow illegal — how would artists get paid?

Other streaming services hit the market too soon after, with Tidal launching in 2014, Apple Music in 2015, just to name the big players. At this point in time, MP3 players had fallen off completely in popularity. Apple stopped making the iPod Nano and iPod Shuffle in 2017, and ended the iPod legacy by finally discontinuing the iPod Touch in 2022.

Now that streaming is the main way people consume music, it’s worth looking at how streaming compares to the bygone era of digital audio players. What did we gain, and what did we lose, by moving into the streaming era?

What did we gain, and what did we lose, by moving into the streaming era?

Even more music directly at our fingertips

The most obvious gain we got from music streaming is the fact that you can stream practically anything you want at any time at no added cost. If your favorite artist is on the streaming service you use (which is extremely likely), you’re likely a happy listener. You can save thousands of songs from countless artists, create playlists easily, and dive into anything you want.

Music discovery is also a lot easier this way, since you can sift through genres and playlists and look at artists similar to the ones you already like. Most streaming services also curate playlists for you based on your listening habits and recommend new songs to you all the time. This is so much easier than having to organically discover new music, through word of mouth or seeking it out actively online or in store.

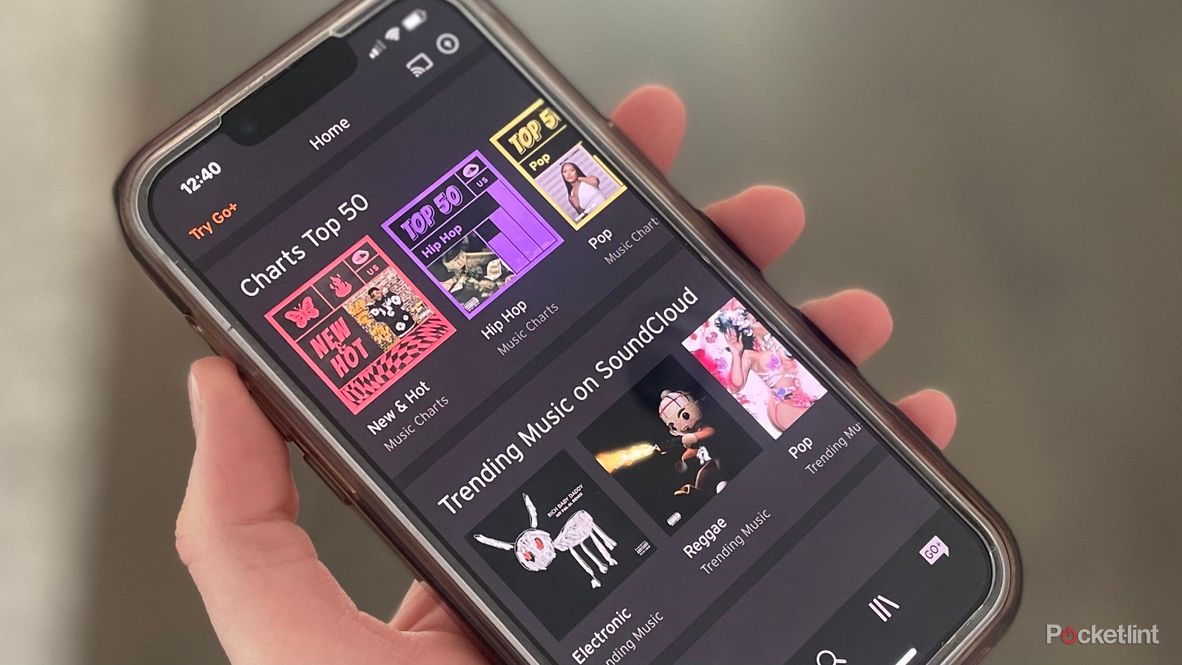

Why SoundCloud beats Spotify for discovering underground music

Some of the most popular musicians had humble SoundCloud beginnings, and the platform has more talent to discover with its access to niche artists.

But music being this accessible comes with a major caveat for artists — they’re not paid like they used to be. Artists used to make a lot more money off album sales, and now they make fractions of a cent per stream. Only the most popular artists see much return from their music being streamed, while smaller artists suffer and may never turn a profit.

Music quality

In the days of listening to physical CDs, listeners experienced high quality lossless audio from those disks. But once you put them on an iPod, those files were compressed and lost a lot of data. If you had a digital audio player that supported higher bitrate, CD-quality audio files, then you were certainly still getting that good quality music, but let’s face it, most people were using iPods, which didn’t support any lossless codecs until the third generation, when the iPod got ALAC support. But considering most people were downloading MP3s on their iPods, the audio quality situation could’ve been a lot better.

Adrian Sobolewski-Kiwerski/ Pocket-lint

By contrast, major streaming services like Apple Music, Tidal, and Amazon Music Unlimited have lossless audio streaming. This makes lossless music more accessible to more people at once, so people can enjoy better quality music more easily and wherever they want.

Lossless audio might be coming to Spotify. Here’s what we know

Spotify HiFi keeps getting delayed, so what gives?

Disincentives piracy

In the early 2000s, piracy was an issue. Downloading individual songs –or even whole albums — was an expensive feat, especially after Apple hiked its prices from $0.99 to $1.29 per download in 2009. Many found it “easier” to downloa and load music on a digital audio player compared to dropping up to $13 for just 10 songs, which is significantly less than one of my current Spotify playlists.

Similarly, many found it “easier” to open up Limewire and pirate an album than it was to go to the store and buy the CD, despite its illegality.

The era of streaming ushered in a new kind of convenience for music listening, plus the lower up-front cost of paying for a streaming service compared to buying albums made it the more appealing lawful option. After all, piracy is less convenient than paying $10.99/ month for Spotify Premium.

Ultimately, as long as the internet exists, piracy is unavoidable, but streaming is a strong disincentive. Add in the social element of paying for a streaming service, like getting to share your Spotify Wrapped every year, seeing what your friends are listening to, and making shared playlists, and streaming is the much more appealing option.

How to kick off a Spotify Jam session with your crew

With Spotify Jam, you can get a collaborative music experience, where you and your friends co-create playlists and listen together from anywhere.

Modern listening

Modern listening

Do we have to choose between intentional listening and convenience?

We live in a much different world than we did in 2001 in so many ways, and the state of personal audio listening is no exception. Instead of 1000 songs in your pocket, we have 100 million, and they’re more accessible than ever. However, this means that the state of the music industry is fundamentally different, and it’s more difficult than ever for artists to get money for their hard work. With the acceleration of technology there are going to be massive trade-offs for convenience, but for those who resent what those tech advancements have brought us, you still at least have the option to use a digital audio player as an alternative. Even though most of the world has moved into the streaming era, that option can never be taken away from you. For better or for worse, streaming seems to be the state of music consumption that looks like it’s here to stay for a long while.