The first confirmed owner of the Voynich manuscript was George Baresch, an alchemist from Prague who had mentioned in a letter that he had found it in his library ‘taking up his space’.

He learned that Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher, in Rome, had published a Coptic dictionary and claimed to have deciphered the Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Baresch sent a sample copy of the script to Kircher, asking for clues to reveal what the mysterious manuscript meant.

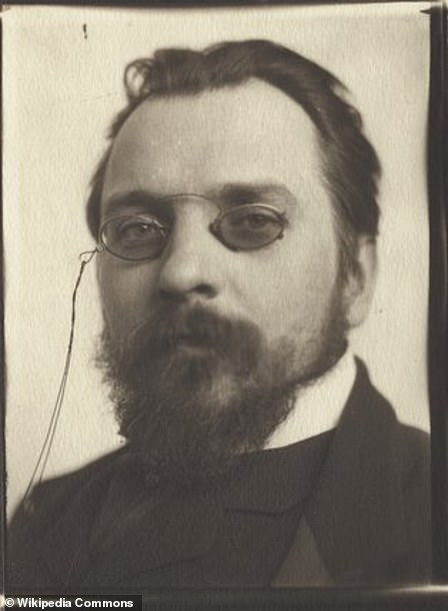

It was purchased in 1912 by a Polish-American antiquarian book dealer, named Wilfred Voynich (pictured) (1865–1930), from where it gets its name

His 1639 letter to Kircher is the earliest confirmed mention of the manuscript that has been found to date.

Kircher asked for the book, but Baresch would not yield it as he prized owning it over knowing its true meaning.

Upon Baresch’s death, the manuscript passed to his friend Jan Marek Marci, who worked at Charles University in Prague.

A few years later, Kircher finally got his hands on the book when Marci sent it to him as he was a longtime friend and correspondent.

When Johannes Marcus sent it to Kircher, they found a letter written on August 19, 1665 or 1666 inside the cover.

It claims that the book once belonged to Emperor Rudolph II, (1552-1612) who paid 600 gold ducats (about 4.5 pounds of gold) for it.

The letter was written in Latin and had been translated to English.

The litany list of previous owners trying to unpick its secrets continues even further, as the manuscript embedded itself further into European folklore.

The manuscript is also thought to have once been in the possession of ‘Jacobj aTepen’, or Jakub Horcicky of Tepenec, a medical doctor who lived from 1575-1622 and was known far and wide for his herbal medicinal use.

No records of the book for the next 200 years have been found, but in all likelihood, it was stored with the rest of Kircher’s correspondence in the library of the Collegio Romeo.

It likely remained there until the troops of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy captured the city in 1870 and annexed the Papal States.

It was purchased in 1912 by a Polish-American antiquarian book dealer, named Wilfred Voynich (1865–1930), from where it gets its name.

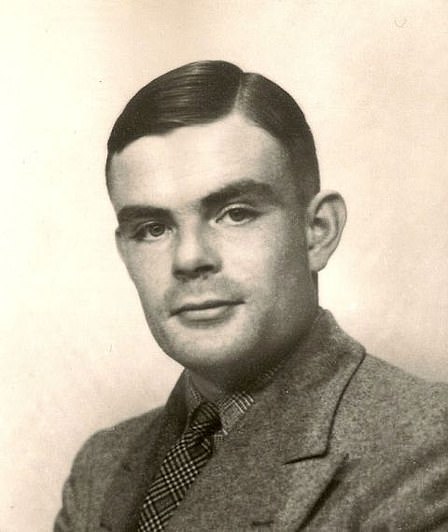

Alan Turing (pictured), the brilliant mind who spearheaded the campaign to crack the Enigma code at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, attempted to understand it, but found it impenetrable

His acquisition of the manuscript is different to its previous owners, from whom it was passed from hand to hand.

According to folklore, he happened upon a trunk that contained the rare manuscript now known as the Voynich manuscript while on an acquisitions trip.

He had it in his possession until he died, and put it on display to the public for the first time ever in 1915.

It further etched itself into folklore and the mystery surrounding it deepened form this point onward as its uncrackable code attracted the greatest minds for decades – all trying to uncover its meaning.

Wilfred subsequently relocated from Europe to New York and, following his death, the manuscript’s custodian became his wife Ethel Voynich (1864–1960).

Following her death the manuscript found its way into the hands of another dealer named Hans P. Kraus (1907–88), who eventually donated it to the Yale library in 1969.

Alan Turing, the brilliant mind who spearheaded the campaign to crack the Enigma code at Bletchley Park during the Second World War, attempted to understand it, but found it impenetrable.

Theodore C Peterson, a priest, embarked on the project of making a hand copy of the Voynich manuscript.

He completed it in 1944 and each page of the replica points out unusual features, which may be of interest in trying yo decipher it, such as odd character sequences and frequently used words.

He worked on the Voynich until his death and it helped a Danish botanist and zoologist, Theodore Holm of the Catholic University, totentatively identify 16 plant species in the Voynich.

William Friedman (1891-1969) is remembered as one of the world’s foremost cryptologists and became involved with the Voynich in the early 1920s when he corresponded with its namesake.

During his work, he developed the theory that the Voynich manuscript represented a text in a synthetic language (using or describing inflection).

It took Research Associate Dr Gerard Cheshire, pictured here, two weeks, using a combination of lateral thinking and ingenuity, to identify the language and writing system of the famously inscrutable document, he claimed

John Tiltman was a British intelligence specialist, working in association with William Friedman.

Friedman asked Tiltman for his opinion on the Voynich MS text, and sent him copies of the final quire.

He concluded that the text is far too complicated to be the result of a simple cipher and be the results of applying a standard cipher to some plain text.

He spent some time discussing the option of a synthetic or ‘universal’ language as proposed by Friedman.

The FBI also tried during the Cold War, apparently thinking it may have been Communist propaganda.

The US National Securities Agency collaborated with German code-breaker Erich Hüttenhain based on the earlier work of British code-breaker John Tiltman because they had a notion that it might contain communist propaganda.

Ultimately, a consensus emerged: that the manuscript was either impossible to solve or else written in gibberish, as an elaborate practical joke.

Dr Gerard Cheshire, a researcher at the University of Bristol, claimed that it was written in a dead language – proto-Romance – and then by studying symbols and their descriptions he deciphered the meaning of the letters and words.