The urgent need to repair a tunnel damaged by Superstorm Sandy is reigniting tensions between LIRR and Amtrak officials. At stake: the commutes of tens of thousands of train riders who pass nine stories beneath the East River each day, and the best way to fix 115-year-old arteries relied on by three railroads.

The long-delayed effort by Amtrak to repair damage in two of the four rail tunnels running to Penn Station will mean keeping one tube closed through late 2027 at the earliest. While all sides agree the repairs are needed, the method of carrying them out is being fiercely contested.

Amtrak, which owns the tunnels, insists a full-time tunnel outage is necessary to do the job right. The Long Island Rail Road, which runs most of the trains into and out of Penn, is pushing for the work to be carried out primarily on nights and weekends. The LIRR is warning customers that Amtrak’s approach could result in major service meltdowns during the rush hours, especially if another tunnel unexpectedly goes out of service.

Ahead of the tunnel closures scheduled to begin Friday, here’s a primer on the issues, including the worst case scenarios for riders and taxpayers.

WHAT NEWSDAY FOUND

- Amtrak and LIRR officials agree that two of the four East River rail tunnels running to Penn Station need repairs, but the two sides are bickering over how the work should be done.

- Amtrak, which owns the four tunnels, says to save time and money each of the Line 1 and Line 2 tunnels slated for the repairs should be fully closed while work is underway, starting with the Line 2 tunnel.

- LIRR argues the work should be done primarily on nights and weekends, saying a complete Line 1 or Line 2 tunnel shutdown would push some Amtrak and NJ Transit trains into the Line 3 and 4 tunnels which LIRR typically has to itself, potentially causing major service disruptions.

Two of four crumbling East River tunnels stretch from Long Island City, Queens to Penn Station.

Floodwaters from the Oct. 29, 2012, Superstorm Sandy inundated two tunnels and left behind corrosive chemicals from the saltwater that have continued to eat away at the concrete structures. On a recent tour for members of the media, Amtrak officials pointed to crumbling concrete, water leaks and corroded steel as byproducts of Sandy.

Amtrak hoped to start the work by 2019. But several factors delayed it, including uncertainty over funding and an agreement between Amtrak and the Metropolitan Transportation Authority to wait for Grand Central Madison to open, which gave the LIRR a second route onto and off Manhattan through other tunnels further north.

After inspecting and making spot repairs to the 115-year-old East River tunnels, Amtrak says it needs to fully shut down tunnels for long-term fixes. The work was supposed to start in November, but has been has been postponed because of delays to an MTA infrastructure project in Queens that must be completed first. MTA officials have suggested the Friday start could be pushed back further.

“It’s critical that we don’t keep punting, because the danger is that we jeopardize our ability to continue to run safe and reliable service through the East River tunnels,” Amtrak executive vice president Laura Mason told Newsday in an interview earlier this month.

Amtrak engineers said only performing East River Tunnel work on nights and weekends would add to the project’s $1.6 billion cost and extend the timeline. Credit: Ed Quinn

The LIRR rarely uses the damaged tunnels, but it still matters for riders.

The two tunnels pegged for repairs — known as Line 1 and Line 2 — are primarily used by Amtrak, which runs trains up to Boston over the Hell Gate Line that begins in Queens, and NJ Transit, which stores trains in Sunnyside, Queens. The LIRR, which runs the majority of trains into and out of Penn, typically has Lines 3 and 4 to itself.

LIRR president Robert Free has said with three railroads sharing three tunnels, even minor issues could quickly cascade, leading to major service disruptions. Free’s biggest concern is the potential for another tunnel to unexpectedly go out of service with one already down, leaving the LIRR with just one tunnel and Amtrak and NJ Transit sharing the other one.

That would lead to a suspension of LIRR trains to Penn, because service is “not sustainable with one tunnel,” Free said at a May 7 news conference.

Amtrak’s not just repairing the tunnels, it’s upgrading them.

In addition to repairing Sandy damage, Amtrak is taking the opportunity to upgrade and modernize the century-old tunnels. That’s what it’s been doing with much of its Penn Station track infrastructure beginning in what Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo called 2017’s “Summer of Hell,” which followed several infrastructure failures in the station and tunnels.

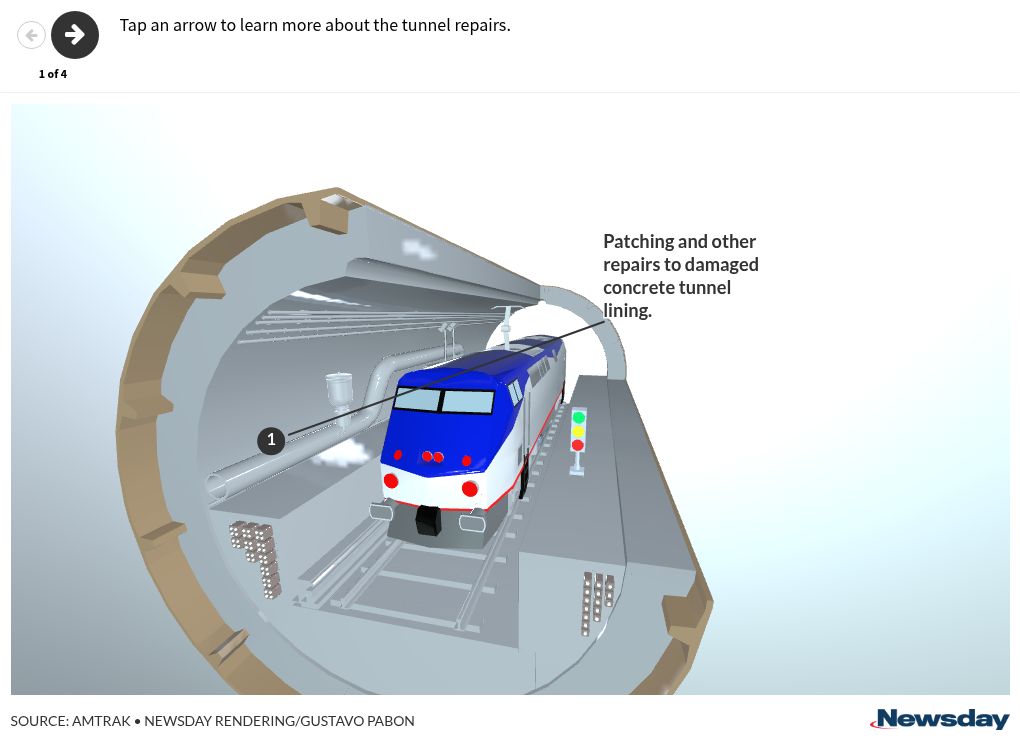

The $1.6 billion tunnel work, which is largely being funded by federal grants, includes demolishing the tubes down to their concrete liners, then rebuilding them with several improvements, including lowering “bench walls” that train passengers can walk on during emergency evacuations. The crushed stone, or “ballast,” that has long been used as the track foundation in the tunnels will be replaced with a concrete slab system. Amtrak will also install new signal, drainage, and fire and smoke detection systems.

Given the scope of the work, Amtrak says a full-time shutdown of the tunnels is necessary. Line 2 would first be down for about 13 months. About three months later, work would begin on Line 1, which would be closed for another 13 months, according to Amtrak. Amtrak has suggested it could take longer than projected.

MTA says the tunnels can be fixed without shutting them down

The MTA has pointed to its 2019 effort to repair Sandy damage inside a subway tunnel in Canarsie, Brooklyn, as a potential model for how the East River tunnel work could be done without a prolonged outage. A key difference in the strategies is that rather than encase power cables in concrete, the MTA mounted them on racks on the tunnel walls.

“You’ve got to adjust your scope so you don’t create an environment that requires a full shutdown,” MTA chairman Janno Lieber said at an April 29 meeting.

Amtrak president Roger Harris, in a May 2 letter to Gov. Kathy Hochul, said the differences between the two tunnel projects “are substantial.” For one thing, Amtrak’s electric cables carry a much higher voltage than the subway’s, necessitating them being encased in concrete for safety reasons. Instead of the “patch” job approach the MTA favors, Amtrak says it wants its repairs to last for the next 100 years.

LIRR’s Free has suggested a compromise, with longer tunnel outages when ridership is low, including the beginning and end of the work week and during summers. Mason, the Amtrak executive vice president, said the MTA’s approach could add years to the timeline and make it “cost a lot more.”

An LIRR train travels east inside an East River Tunnel. Credit: Craig Ruttle

The risks would be far greater if it weren’t for Grand Central Madison.

Although the LIRR is losing one tunnel under the East River, it will still have one more than it did it just a few years ago, thanks to the completion of the MTA’s $11 billion East Side Access megaproject, which gave the LIRR two new tunnels linking to Grand Central Madison.

“That is a huge plus in this circumstance,” Lieber said. “If we didn’t have Grand Central Madison, it would be a potentially catastrophic situation.”

While having Grand Central Madison lessens the overall impact of Amtrak’s tunnel closure, LIRR officials note about 60% of its Manhattan commuters are still bound for Penn Station. The percentage of riders using Penn Station is even higher during off-peak hours.

The rift between Amtrak and the MTA is about more than just this project.

The peculiar arrangement between Amtrak and the MTA at Penn Station has long bred animosity between the two transportation agencies.

Amtrak owns and is responsible for Penn and the adjoining tunnels. But the LIRR, as the primary user, is legally required to cover much of the cost of maintaining Penn’s infrastructure. That’s led to frustration by the MTA when infrastructure failures disproportionately impact LIRR customers.

The East Side Access project, which created Grand Central Madison, further strained the complicated relationship, as the MTA said many of the delays and cost overruns were due to Amtrak not providing the manpower it promised.

Both sides have also clashed over their visions for the future of Penn Station, which is in line for a multibillion reconstruction.

Until recently, the MTA — a state public authority — led that effort, and was expected to prioritize customers of the LIRR and Metro-North, which plans to soon connect to Penn. But, last month, President Donald Trump’s administration, which has been fighting with the MTA over its congestion pricing program, announced it was taking control of the project along with Amtrak, a quasi-federal entity.

LIRR president Free has also accused Amtrak of “poor maintenance practices” that have resulted in infrastructure failures and give him little faith the forthcoming tunnel repairs will go off without a hitch.

Amtrak has said it’s stepped up maintenance efforts in recent years, and is doing everything necessary to ensure the remaining tunnels don’t fail while one is already out of service.